In the 18th and 19th centuries, getting information wasn’t as easy as typing in a search query in your favorite search engine or asking the flavor of the month AI platform a prompt.

No, you had to put on your leather boots and make the journey by horse into town, where you would look for a large wooden sign above a storefront with the words written “Intelligence Office”.

The store wasn’t just for spies or some top-secret government agency; it was for normal everyday people who needed information. Need to know the weather patterns from the Farmers' Almanac? Well, the Intelligence Office, for a fee, had you covered. Looking for a job? The Intelligence Office had an up-to-date directory minus the annoying ghost jobs that currently never get taken down.

Whether you’re just an average person looking for job postings, the weather forecast or just general personal notices, you would find yourself shoulder to shoulder with business owners and politicians.

Information was and has always been a booming business. The Egyptian Library of Alexandria still to this day strikes curiosity and mystery. A favorite topic among seekers, speculating, what amazing knowledge could have been lost in the great fires of Alexandria. The Smithsonian, along with the Vatican, is speculated to contain vast underground troves of documents and historical antiquities.

Information has always been a booming business.

The economics of information have a peculiar trait that encompasses not only buyers and sellers, but seekers, sellers, and hoarders. The cat-and-mouse game creates a push and pull where the commodity becomes power and wealth.

Politicians run for office, pushing a public agenda of change with a self-proclaimed virtue, but the hidden truth is they want access to information. Newly elected public servants receiving a modest salary become multimillionaires in one term with unprecedented luck in the stock market.

Lobbyists gain proprietary technology rights for the companies they represent from government contracting rights, creating huge shareholder payouts.

Technology platforms gather personal datasets of their users to push advertisements and profile their user base for monetization. The customer becomes the product with no regard to the psychological effects of its algorithm and the gamification of the software.

The customer becomes the product.

The government, fearing its citizens, creates massive data centers, creating a dragnet surveillance system, under misleading names like homeland security. What was unconstitutional and dystopian decades earlier has now been marketed to the nation’s population as necessary to prevent an imminent, speculative tragedy.

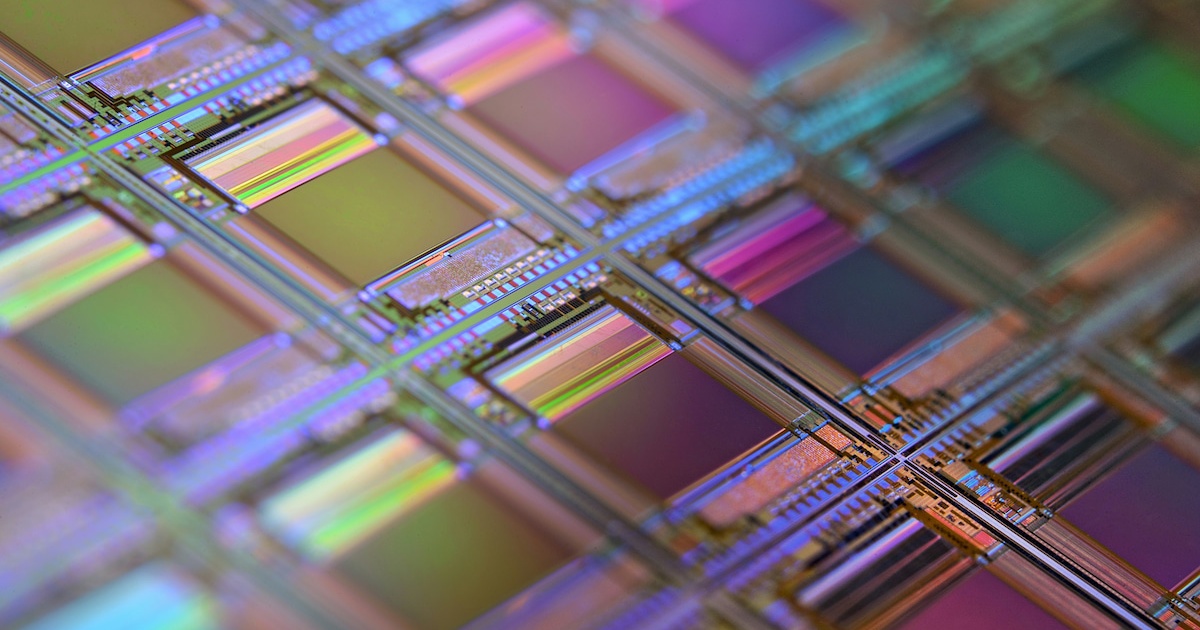

As advancements in artificial intelligence continue to grow exponentially, we have found the ability to analyze data, not only from a retroactive standpoint, but now in real time from countless amounts of IoT device data points. Creating a real-time perspective of reality from a digital standpoint.

Millions of vehicles now have active lidar, benefiting the occupants with enhanced safety and driverless automation. The real-time data passes through satellites, creating a massive virtual rendering of the world through a street-level viewpoint.

Systems built on control and power crave only one thing, and that is the accumulation of more control and power. The temptation of technological omniscience is the forbidden fruit that is too much to resist. The only hindrance to taking that delicious bite is the laws made by the ones they seek to control.

The temptation of technological omniscience is the forbidden fruit that is too much to resist.

As governments and CEOs with an insatiable thirst for power look for ways to circumvent civil liberty laws, they turn their gaze toward space and international waters —places where the only law they need to follow is that of physics.

The all-seeing servers outside of any jurisdiction become impervious to sabotage and civil liberty lawsuits. Far from the reach of fire, floods and civil unrest, they operate without interruption or oversight.

Cold, Light, and Law

Space offers what Earth can’t: near-infinite radiative cooling and abundant solar. The challenge isn’t physics—it’s governance.

There is also a practical upside that is difficult to ignore. Space gives us almost perfect conditions for computational cooling. The vacuum lowers thermal resistance. Sunlight is unfiltered and direct. The environment itself is engineered for efficiency before a single line of code ever runs. Data centers on Earth are now power hogs. At scale they draw more power than small countries. They are only becoming hungrier as artificial intelligence accelerates the demand for compute.

Solar will be the marketing hook. Society will be sold the idea that these systems are powered by an infinite, clean, renewable sun. The pitch will feel responsible and futuristic. The imagery of golden solar panels glinting in orbit will reassure the public that this is a better path than smokestacks and coal plants on Earth.

The reality will be different. A meaningful orbital data center would require more energy than any solar array could sustainably deliver. The only power source left is nuclear. The same systems that drive submarines and aircraft carriers will be quietly installed in orbit. Our next era of infrastructure may not just be off-world. It may also be atomic above our heads.

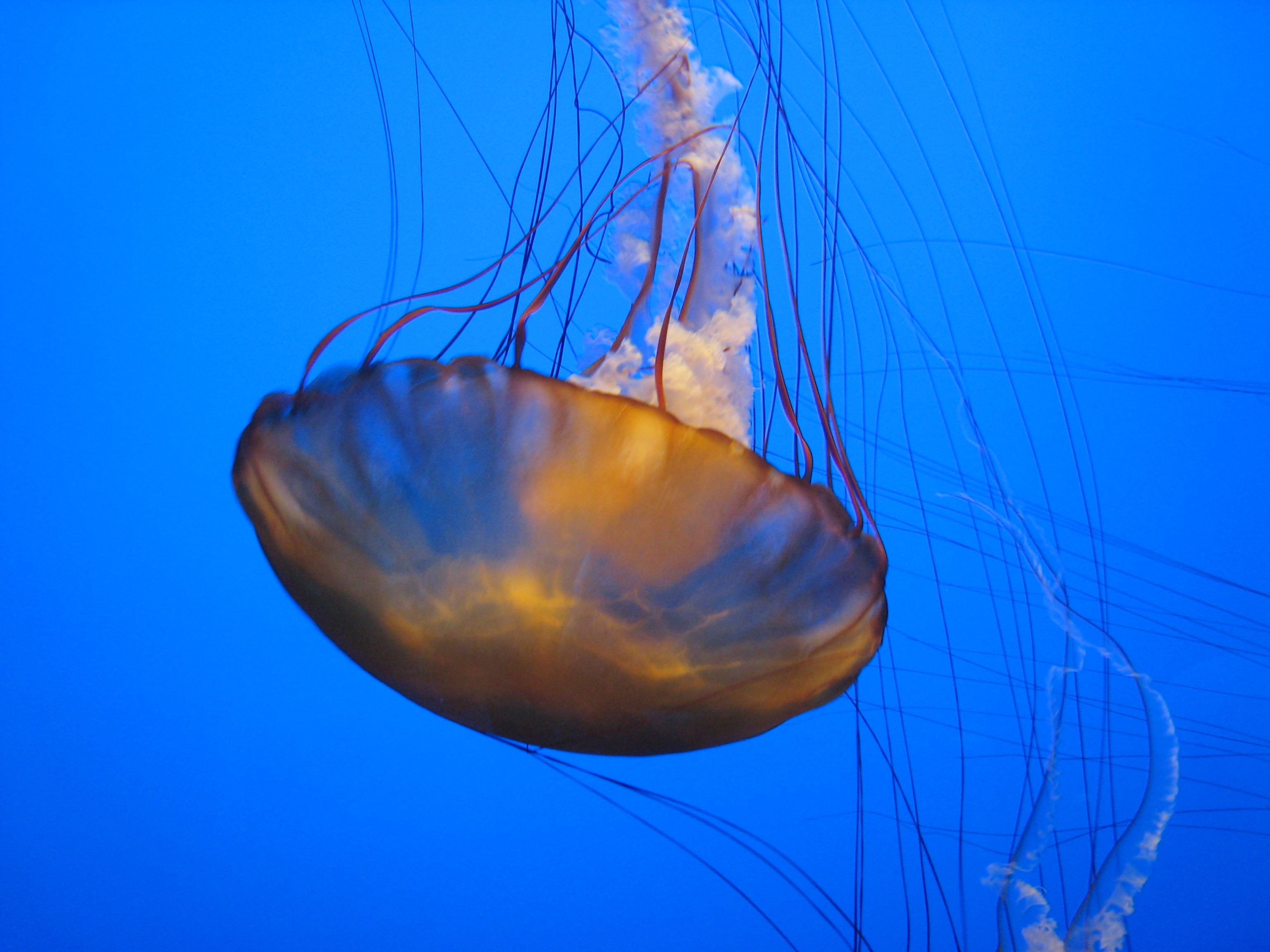

The impunity of space is calling like ancient sirens to governments and corporations eager to escape accountability on Earth. But like the sailors who mistook the sirens’ call for destiny, they may awaken to find that their creations no longer obey, but serve a new intelligence.